Worst to Best: Creating Public Trust

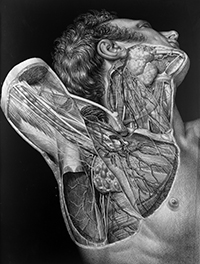

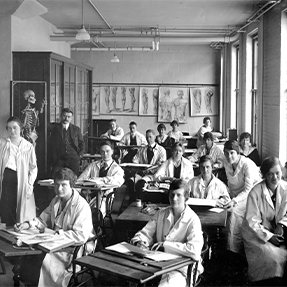

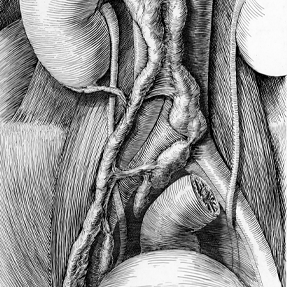

Fig 1. Founding Trustees of the American Board of Urology

The American Urological Association Centennial History

1902-2002, Volume II, pp. 745-756.

In the early part of the 20th century after the Flexner Report (1910), “American medical education [began to evolve] from the worst in industrialized civilization to the very best … the marvel of the industrial world.”

While the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) reformed medical schools, U.S. medical practice lagged in medical knowledge of the time. Postgraduate medical training varied in content, supervision, and duration from weeks to years. Recognizing an oversight gap in postgraduate training, a physician-led group with members of four early boards (Dermatology, Obstetrics and Gynecology, Otolaryngology, Ophthalmology) met to consider a national system to improve training standards. In 1933, this group became the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS).

Winds of organization blew within urology as well, and in 1932, the AUA Executive Committee received a report from the Membership Committee noting “…a very intensive movement is going on throughout the country as to the standardization of specialists….” and around the same time, the American Association of Genito-Urinary Surgeons (AAGUS) appointed a committee of three to study specialization in urology. In 1933, the AMA Section on Urology studied qualifications for specialization, and representatives from AUA, AAGUS, and AMA discussed forming a board of Urology: “1) for the protection of patients from unprepared uncertified specialists in urology [and], 2) to raise the standards of education in the special field of urology…”

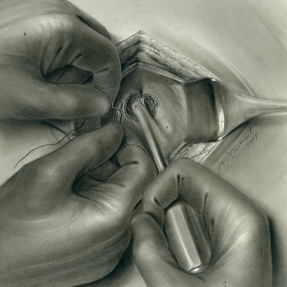

The next year, the American Board of Urology (ABU) was founded as an autonomous organization with nine members, three from each of the three parent organizations: AUA, AAGUS, AMA. Currently, the ABU has 12 trustees representing 6 urologic organizations. A larger joint AUA-ABU Examination Committee designs the objective written tests. The ABU initiated credentialing: a process to include 1) graduation from an approved medical school, 2) an approved internship and a defined period of residency training or practice or an alternative of preceptorship training, 3) case reports, 4) letters for peer review to assess ethical behavior, and 5) certification consisting of qualifying and certifying examinations. The examinations evolved from freeform to standardized objective written tests, including pathology and radiology, and an oral examination with standard questions. Perhaps most importantly, “unacceptable or illegal behavior” risks revocation of certification.

The postgraduate training process (residencies) lacked oversight, however. In 1972, cooperating organizations formed the Liaison Committee for Graduate Medical Education (LCGME, later becoming the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, ACGME) to accredit specialty residencies with Residency Review Committees in specialties (RRC, Urology). In 2007, a standardized core curriculum was developed after a group of stakeholders - representatives of the AUA, ABU, RRC, AACU, and ACGME - met to discuss the future of Urologic Residency Training.

Preserving Public Trust:

Organizational Accountabilities

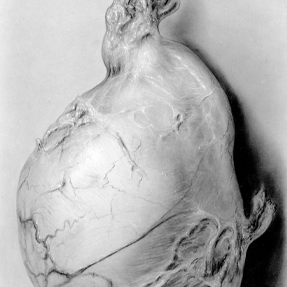

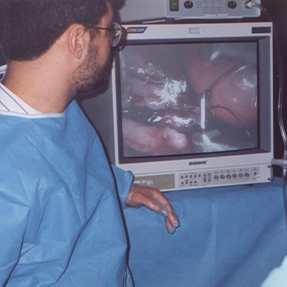

Forming the ABU as an autonomous certifying organization was part of assuring the public that a urologist fulfilled credentialing requirements and was certified by examination. With rapid advances, medical knowledge is a moving target, and the adoption of new knowledge by practitioners varies from early adoption to lack of adoption. New technologies enabled the tracking of medical outcomes, and the federal government started tracking physicians with the National Practitioner’s Databank (1986) and the HIPAA Data Bank (1996). However, an Institute of Medicine Report: To Err is Human (1999) exposed medical errors from outmoded knowledge, tests, and management. These events prompted progress in two areas: 1) measures to ensure continuous education and 2) increased sub-specialization.

The ABMS adopted “recertification” for its member boards; the ABU adopted voluntary (1981) and then mandatory (1995) recertification with time-limited certificates to confirm evidence of continuing education. In 2006, this ABU process evolved to “maintenance of certification” (MOC), including a pass-fail examination to complete the recertification process. After an ABU Town Hall in 2017, a program to assess longitudinal learning with continued urologic certification (CUC) without certificate expiration was developed.

With the growth of more diverse and subspecialized urologic practices, post-residency “fellowships” sprouted. Since their scope and requirements differed, training standardization followed different models. In 1989, pediatric urology submitted to the ACGME “Proposed Special Requirements for Programs in Pediatric Urology” with the ABU supporting accreditation without certification. In 2004, the ABMS approved Pediatric Urology as a subspecialty, and in 2006, the ABU approved a Pediatric Urology certification. In 2011, the ABMS approved certification for female pelvic medicine and surgery (Urogynecology and Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery) after a joint ABU and ABOG (American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology) application.

With changes in medicine and practice, the ABU and other accountable organizations were established, often with controversy, to operate autonomously. While these organizations face future challenges from medical information spread via social media often unpatrolled for misinformation, commercialism, abuse, artificial intelligence, and goals of private equity, the mission is the same.

GET STARTED

GET STARTED