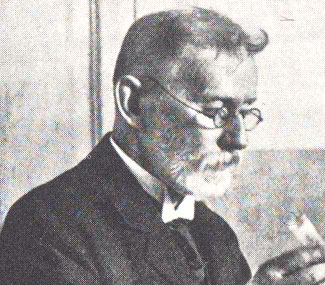

Paul Ehrlich (1854-1915) was born in Strehlen, Silesia on March 14, 1854. During his college years in Breslau, he showed an interest in chemistry and histology courses.

In 1873 he moved to the University of Strassburg, where he was tutored by Professor Waldeyer. It was there he discovered a cell with granules that could be selectively stained, which he called the "mast cell." Ehrlich felt he had a special talent for picturing abstract chemical concepts, and he envisioned many things in chemistry which later were developed. Again in Breslau, he worked in the laboratories of Heidenhain and Cohnheim and befriended William H. Welch. At 24 he obtained his MD degree from the University of Leipzig for presenting a thesis entitled "Contributions to the Theory and Practice of Histological Staining."

During the next 10 years Ehrlich worked at Professor Frerichs' clinic at the Charite Hospital in Berlin.When Ehrlich heard of Robert Koch's discovery of the tubercle bacillus, he devised staining methods for this bacillus. Over the course of these years at Frerichs' clinic, he published more than 40 papers and his first book, Oxygen Requirements of the Organism.

Ehrlich contracted tuberculosis, and went with his wife to Egypt to recuperate for two years. He returned to Berlin in 1889 and set up a little private laboratory to pursue his own ideas. Robert Koch soon offered him a place in his newly founded Institute for Infectious Diseases. During this period Ehrlich studied bacteriology and tried to learn more about the special affinities of certain chemical compounds to parts of bacterial and cellular protoplasm.He met Emil von Behring who had discovered specific immune substances in the blood serum of animals infected with diphtheria or tetanus bacilli. When Behring had difficulties in producing clinically reliable antisera, Ehrlich developed methods to produce higher effective titers and a reliable means of measurement in units which are still valid. Ehrlich also formulated his "side chain theory" to explain the phenomenon of specific affinities between toxins and antitoxins.

In 1896 Ehrlich was invited to become director of the new State Institute for the Investigation and Control of Sera in Berlin-Steglitz. Ehrlich so impressed the Director of the Prussian Ministry of Education and Medical Affairs, he and the Lord Mayor of Frankfurt-am-Main founded a large Institute of Experimental Therapy at Frankfurt/Main. In 1899 he took charge of the new Institute and made most of his greatest discoveries and contributions in the last 16 years of his life. In 1904 he produced trypan red which was effective against trypanosomes, especially those causing sleeping sickness.

When Thomas and Breinl discovered atoxyl and found it to be effective against trypanosomes, but highly toxic to the optic nerve, Ehrlich directed his efforts toward finding a more effective but less toxic derivative. In 1906 Ehrlich and his staff produced their 418th preparation, arsenophenylglycin, a most potent substance against tropical diseases caused by trypanosomes.

Ehrlich tested his arsenical preparations on animals infected with the spirochete that causes syphilis. Dr. Hata came to work in Ehrlich's laboratory, infecting rabbits with syphilis, testing compounds for its effects on infected rabbits. One compound, 606, was eventually given to clinical investigators for trial on patients.

A doctor from St. Petersburg Hospital reported that 606 (Salvarsan) cured patients with relapsing fever, and Dr. Schreiber from the City Hospital at Magdeburg described the first successful syphilitic treatment. Ehrlich promoted intravenous injection to avoid local reactions and worked with all of his energy to perfect a safe therapy.

He had many outstanding investigators work in his laboratories or visit him, and among the many honors he shared the Nobel Prize for Medicine with Metchnikoff in 1908. Slander, libel, and anxiety about the "madness of the war in 1914" saddened his last years. An early death following two strokes in 1915 interrupted most fertile life and his further research in chemotherapy.

Contributor:

Matthew Kaag, MD